During the COVID-19 pandemic, many barriers to telemedicine and access to remote doctors were removed to meet emergency healthcare demand. Most states relaxed in-state licensing requirements for physicians and treatment and reimbursement restrictions were modified by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). These temporary changes opened doors to patient care and telemedicine.

For underserved rural and community hospitals, broadening telehealth services across state lines offered critical physician resources essential to fight the pandemic. It also expanded access to many medical specialties that were critical to treating coronavirus patients — many that aren’t typically available outside metropolitan areas. However, the need for such access still exists.

As cases of the coronavirus continue to rise and epidemiologists predict a second wave of hospitalizations, we focus again on the importance of access to specialists in rural and mid-sized communities across the country. In fact, the need for specialist care and greater hospitalist coverage will remain long after a vaccine or treatment for the coronavirus is available.

The national physician shortage is estimated to reach 122,000 open positions by 2032. Additionally, making access to care consistent regardless of race, insurance coverage or location, the country would require approximately 100,000 more physicians. Today, the shortage is already a reality in rural and underserved communities where specialists and general practitioners are not readily available 24/7/365, and in some cases, not available at all.

In light of these issues, there’s an obvious need to simplify the physician licensing process to improve patient access to remote doctors across state-lines.

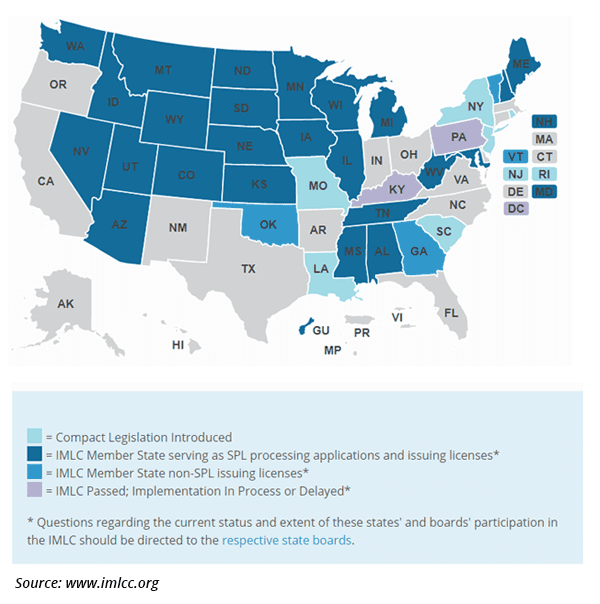

One avenue for erasing state boundaries in physician licensing is the Interstate Medical Licensing Compact (IMLC), an agreement among participating U.S. states to streamline the licensing process for doctors outside their State of Principle License (SPL). Expansion of the IMLC would make it easier for physicians to obtain and hold medical licenses in multiple states — a step towards solving the physician shortage and enabling a wider, easier adoption of inpatient telemedicine programs.

The Licensing Dilemma

In 2018, there were 985,026 licensed physicians in the U.S., according to the Federation of State Medical Boards’ (FSMB) biennial census. Of those, 15% had two state licenses and 7% had three or more; just 14 physicians had licenses in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Those numbers have remained relatively unchanged since 2010.

Outside of emergencies, state-by-state licensing can take months and be quite costly. As noted, 49 states authorized individual waivers addressing telemedicine amid the COVID-19 crisis. Looking long-term, physician licensing would benefit from a single national standard.

“Telemedicine is a specific innovation particularly hampered by the status quo,” wrote two board-certified family physicians in a recent issue of Modern Healthcare. “Even in this time of crisis, the rules vary state by state (and keep changing). For example, physician colleagues at Jefferson Health in Pennsylvania, a pioneer in telemedicine, have had to apply, pay for and maintain licenses in as many as two dozen states in order to provide seamless access to patients.”

Enter the Interstate Medical Licensing Compact

Given the cost and complexity of holding multiple state medical licenses, it became increasingly evident that a better process was needed. Technical advances, like telehealth, offered a realistic way to improve care at rural and community hospitals. State regulations that limit care from a remote location were designed to protect patients and regulate healthcare quality within each state. However, the physician licensing processes and state regulations for medical providers were written at a time when providing patient care from a distance was science fiction.

To address these archaic processes and bring consistency to physician licensing, a group of state medical board executives, administrators and attorneys launched the IMLC in 2014. The introduction of the Compact was a means of simplifying the medical license application process for physicians who want to practice in multiple states. Individual state legislatures began adopting the Compact in 2017.

The Compact defines the role of the IMLC Commission — the governing body that administers the Compact on behalf of participating states. While this commission does coordinate multi-state licensing activities, the individual licenses are still issued by participating states.

Physicians in good standing from a participating state can qualify to practice medicine across state lines if they meet the Compact’s eligibility requirements, and around 80% of U.S. physicians meet the criteria for licensure through the IMLC. These eligible remote doctors can qualify to practice in IMLC-participating states by completing just one application, and then they receive separate licenses from each state where they plan to practice.

While the IMLC is a compelling idea for improving care at rural and community hospitals, there is still a long way to go. Although there are just 29 participating states, the IMLC has issued at least 7,000 state medical licenses to over 4,500 physicians. It is unclear how many of these were for telehealth purposes, because the IMLC does not track this statistic.

Limitations of the IMLC

Despite the advantages of participating in the IMLC, critics of its structure and processes remain. Here are some of the perceived disadvantages hindering the inclusion of telemedicine care within the IMLC.

- Lack of license portability: Remote doctors who practice in multiple states have to adhere to a variety of state-specific medical practice regulations. They also incur an IMLC membership fee plus annual license renewal fees for each state license, which may discourage physician participation. The initial cost to participate in the IMLC is $700 plus the cost of license(s) in each state, which range from $75 to nearly $800.

- Practice location limits: By sticking with a state-based approach to medical licensing, the IMLC perpetuates barriers to telemedicine. Changing the site of practice from the patient’s location to that of the physician would remove these barriers, but would require an act of Congress and is opposed by the AMA.

- Cost prohibitive: Private companies may offer a competitively priced solution to help physicians apply for state licenses and could potentially replace the more expensive federally subsidized IMLC.

- Database issues: The law enacted by participating state legislatures tasked the IMLC with creating a database that tracks sanctioned doctors. Reportedly, progress on the database has been slow due to its complexity, and the information is already tracked through the National Practitioner Data Bank and Federation of State Medical Boards.

The overarching argument against the IMLC by some critics is that it is not true interstate medical licensing because of portability and practice limitations noted here. Proponents, such as the Execuitive Director of the IMLC Commission, Marschall Smith, argue that state-based licensure provides local accountability that “is naturally more responsive to the necessary balance of patient and physician protections.”

Global Crisis Demands Global Response

State lines aren’t the only borders that restrict physician practice. Almost one-third (31.8%) of all physicians specializing in family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics are foreign-trained. Although already skilled in diagnosing and treating patients, U.S. licensing requirements forces these remote doctors to “start over” academically through reeducation and evaluation by multiple agencies and boards. Acquiring and keeping the correct visa is another issue to overcome.

New Jersey and New York have temporarily made it easier for immigrant and foreign-trained doctors to help fight the pandemic. Also, the Center for American Progress has recommended that federal and state policymakers, as well as the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG), work together “to lift barriers and enable immigrant and foreign-trained health care professionals to quickly serve in COVID-19 hot spots.”

Despite some temporary inroads, it’s clearly time for a more permanent licensing standard in the U.S. to address physician shortages and other emerging threats. Combining a more modern licensing process with telehealth, would dramatically improve our country’s healthcare system.

The Future of Interstate Medical Licensing

While it’s true that the IMLC has limitations, especially given the number of participating states, it’s an important step in opening the door for inpatient telemedicine at smaller hospitals, just as the temporary CMS waivers are. Still, a careful, long-term solution to interstate medical licensing is needed.

Whether it is a federally mandated regulation or an opt-in state compact, licensing across state lines is an idea whose time has come in terms of inpatient telemedicine. Why? Telemedicine is a necessary piece in helping solve the puzzle of physician shortage, burnout, access to specialties, and geographic penalties that limits care for at risk and underserved populations.